Alternative Data Compliance & Regulation: Is the EU and UK lagging behind the US?

We recently hosted our annual alternative data conference in London and invited two legal experts to discuss the compliance and regulatory developments related to alternative data in the UK and Europe versus the US. The following article highlights the key takeaways from this discussion.

Sonalini de Zoysa Gunasekera, Legal Counsel at Systematica Investments, and Anna Maleva-Otto, Partner at Schulte Roth + Zabel LLP joined to discuss the complexities surrounding the current state of alternative data compliance and regulation happening in Europe and the UK as opposed to the US. The panelists covered a wide array of topics, including adequate due diligence, material non-public information (MNPI) nuances, regulatory focus in different jurisdictions, technological advancements, and the increased risks related to using alternative datasets. This article summarizes key sections within a follow-up report we published on the subject, You can download the full report from our website here.

Insider Trading and Material Non-Public Information

Insider trading regulations are pivotal for maintaining market integrity in the financial world. In the United States, a robust approach to insider trading involves evaluating the materiality of the information, its non-public status, and the absence of a breach of fiduciary duty. U.S. law emphasizes the provenance of data, ensuring the information has been rightfully obtained and distributed, especially when it concerns sensitive types of alternative data like credit cards or healthcare details.

In contrast, the UK and EU frameworks are structured around the materiality of the information, referred to as ‘price sensitivity’ in the UK, and its non-public nature, with less emphasis on the breach of fiduciary duty. Notably, UK case law, such as the 2013 Hannam judgment, has nuanced the interpretation of materiality, even suggesting that minimal price movements could be significant. Moreover, the concept of public information is more flexible in the UK, where the legality of access can render data as ‘public’, diverging from the US’s requirement for broad dissemination.

The scope of liability also varies, with the US demanding proof of fraud or breach of duty, while UK and EU regulations focus on swift disclosure of corporate information and prohibit trading or sharing undisclosed information. The EU reinforced its stance on market abuse with the Market Abuse Regulation (MAR) and the Criminal Sanctions Directive for Market Abuse (MAD 2014), widening the net over insider trading, unlawful information disclosure, and market manipulation while advocating for transparency and safeguards for whistleblowers.

Panel perspective on alternative data constituting an insider trading risk: Anna Maleva-Otta of Schulte Roth & Zabel mentioned that UK and EU regulators have not focused on alternative datasets under market abuse regulations but acknowledged the risks of information asymmetry and insider trading stemming from it.

Data Provenance

In the realm of insider trading in the United States, the legal structure is hinged on three fundamental criteria. To pursue a case, there needs to be material, non-public information involved, and it must be obtained in a way that breaches a duty of trust or confidence. However, this framework presents challenges when dealing with certain types of alternative data. For instance, with credit card information, regulators hit a stumbling block; although such data is non-public and material, the acquisition of this type of alternative data does not necessarily violate any duty because credit card companies’ terms, like those of Mastercard, explicitly permit the sale of their data to third parties. This nuance means that the third crucial box – breach of duty – often remains unchecked in these scenarios.

The UK’s approach diverges by placing the onus on the individual purchasing data to ensure that it is not compromised by insider trading considerations. The assessment revolves around whether the information is sufficiently disseminated to be considered public or whether it is too vague to yield an unfair trading advantage. In the European Union, an emerging initiative that may impact the landscape of data handling and insider trading is the ProDIS project. ProDIS stands for Provenance for Data-Intensive Systems and aims to create a framework to trace the origin and flow of data comprehensively, thus ensuring that computational outcomes can be transparent and justifiable.

Panel perspective on the ever-evolving technology landscape: Sonalini de Zoysa Gunasekera of Systematica Investments highlighted the use of machine learning in the Due Diligence Questionnaire (DDQ) to vet data providers. But it’s not just compliance with regulations that’s scrutinized. A data provider’s overall reputation is also under review, including through word check searches that encompass factors such as litigation history and fraud, indicating a multi-dimensional approach to evaluating data legitimacy and risk.

Data Privacy

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), enacted by the EU in 2018, stands as the world’s strictest law regarding privacy and security. It holds the authority to impose substantial fines, reaching up to 20 million euros or 4% of global revenue for violations. There continues to be room for different interpretation and enforcement practices among the Member States. There is therefore likely to continue to be significant differences in both substantive and procedural data protection laws and enforcement practices among EU Member States with GDPR in force.

Following the UK’s exit from the European Union, the UK Government has transposed GDPR into UK national law, thereby creating the “UK GDPR”. In July 2022, the UK Data Protection and Digital Information Bill was introduced to Parliament. The most significant reform under this banner is the change to Article 22 of the UK GDPR on automated decision-making. The general prohibition has now been removed; instead, conditions must be met for decisions involving particular category data. The ban is then replaced with a series of safeguards that must be in place.

While there is currently no similar federal law in the United States, frustrating legal and compliance professionals across the country, thirteen states have introduced comprehensive data privacy laws: California, Virginia, Colorado, Connecticut, Utah, Iowa, Indiana, Tennessee, Texas, Florida, Montana, Oregon, and Delaware. However, only California, Colorado, Connecticut, and Virginia’s laws are currently effective.

Some Key Legal Differences

The legal landscape for insider trading has divergent roots and interpretations in the US and the EU, resulting in a contrasting approach to defining and policing the offense. In the US, the framework for insider trading emerged from the judicial interpretation of the Securities and Exchange Act of 1934. This foundation has sown seeds of ambiguity, leading to disputes and varying interpretations, especially concerning what constitutes insider trading offenses. Notably, U.S. courts, through instruments like Section 10(b) and Rule 10b-5 of the Securities Exchange Act, played a pivotal role in carving out insider trading laws. Over the years, the ambit of these laws expanded, casting a wider net to include more than just traditional corporate stakeholders as “insiders” and bringing under its purview those who receive non-public information indirectly. Additionally, the introduction of the tipper-tippee liability has added further layers of complexity, resulting in interpretational challenges and inconsistencies across jurisdictions.

In contrast, the EU’s stance on insider trading is much more black-and-white, given that it’s embedded directly within the Market Abuse Regulation (MAR). It offers a more straightforward delineation of the offense and its constituents. The foundational difference between the two regimes can be traced back to the “parity of information” doctrine, which advocates for equitable access to market-moving information for all investors. While the US has shied away from this doctrine, choosing to tether insider trading to situations where a specific duty of trust exists, the EU, through its MAR, embraces it. The EU’s framework hinges on the principle of fairness, prohibiting trades that leverage non-public information to the detriment of uninformed participants. This ethos suggests an overarching duty for all market actors, devoid of the necessity for a distinct duty to a particular entity.

Materiality, Exclusive Data, and Sensitive Data

In the US, materiality is a key concept under federal securities laws, particularly under Rule 10b-5 of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. Material information is generally defined as information that a reasonable investor would consider important in making an investment decision. In the EU, materiality is a concept that is harmonized across member states through the MAR and the Directive on Criminal Sanctions for Market Abuse (CSMAD). Under these regulations, material information is considered information that, if made public, would likely have a significant impact on the price of a financial instrument.

In the eyes of the SEC, exclusivity is not seen as a breach of regulations but may attract unwanted attention when dealing with exclusive alternative data sets. In the UK, exclusivity requires deeper thought about the alternative datasets and the information being received due to the responsibility of the data buyer. In summary, if you are a buyside data buyer, in the US it is not much of an issue more than firm policy and optics, but in the UK, it can come with larger legal precedents.

In the US, there isn’t a specific category of “sensitive data” outlined in federal law. However, certain types of information are considered sensitive due to specific data protection and privacy regulations. For example, healthcare information protected under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and financial information protected under the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA) are regarded as sensitive data. Additionally, personally identifiable information (PII), such as Social Security numbers, driver’s license numbers, and financial account numbers, is generally considered sensitive.

The EU has a more comprehensive approach to sensitive data, primarily defined in the GDPR. This includes information related to a person’s racial or ethnic origin, political opinions, religious or philosophical beliefs, trade union membership, genetic data, biometric data, health data, and data concerning a person’s sex life or sexual orientation. Processing such sensitive data is subject to stricter rules and usually requires explicit consent from the data subject. The UK largely maintains the GDPR’s definitions of sensitive data.

How the FCA Treats Alternative Data in the Investment Landscape

The Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), the UK’s chief financial services regulator, has recognized the increasing prominence of alternative data in the financial sector. In response, it has embarked on a series of initiatives to provide clarity and regulation. Beginning in January 2020, the FCA released an overview detailing potential market integrity risks posed by alternative datasets. The following March, the body made a call for input on the use of advanced data analytics, with an emphasis on discerning how market participants harness these tools for valuable insights. Concerns emerged, ranging from exclusivity issues, new data-monetizing business models, potential risks from increased algorithmic decision-making without proper oversight, and concerns over information sharing.

Fast-forwarding to 2022, the FCA expressed concerns about market integrity risks when select participants trade on scarcely available alternative data. By August 2023, the spotlight had turned to large firms, with worries about their market power and practices potentially undermining competition and transparency. Parallelly, the UK’s legislative trajectory reflected a shift, with the Data Protection and Digital Information (No 2) Bill advancing in the House of Commons in April 2023. Designed to foster a business-friendly environment, the Bill’s introduction, however, drew attention to its potential implications: expansion of the Secretary of State’s authority, changes to the Information Commissioner’s Office, and concerns over surveillance and automated decision-making.

Panel perspective on alternative data regulation in the UK: Reflecting on these developments, Anna Maleva-Otta of Schulte Roth & Zabel highlighted the FCA’s awareness of potential competition barriers and ethical quandaries surrounding alternative data. The regulator’s intent is clear: to probe deeper into barriers in data access or analysis techniques, which could result in unfair competitive advantages.

Recent Regulatory Changes in the European Union

In 2020, the European Union introduced a strategy focused on prioritizing people-centric technological advancement and upholding European values in the digital domain. The primary goals of this strategy were to introduce a unified data market, which would boost Europe’s global standing and promote data sovereignty, and to develop shared European data spaces. These spaces would increase the accessibility of alternative data for both economic and societal benefits while ensuring that those alternative data providers who generate data retain control over it.

In April 2023, European legislators proposed new copyright rules for generative artificial intelligence (AI), requiring companies deploying such tools to disclose any copyrighted material used to develop their systems. Under the proposals, AI tools will be classified according to their perceived risk level, with companies required to be highly transparent in their operations when deploying high-risk tools. Though such tools will not be banned, areas of concern could include biometric surveillance, spreading misinformation, and discriminatory language.

By September 2023, following a 15-month grace period, the European Data Governance Act was implemented. This act was designed to fortify trust in data sharing, enhance data availability, and minimize technical obstacles hindering data reuse. The act championed the establishment of shared data spaces across various sectors such as health, energy, agriculture, and finance, involving both public and private stakeholders. In tandem, the Data Act of November 2020 was introduced to delineate the conditions and entities entitled to extract value from data. It sought to encourage data sharing, heighten trust, amplify the data economy within the EU, and grant users enhanced control over data from connected devices, all while fostering innovation.

Final Thoughts

This report highlights the differences between investment data regulation regimes in the US, the UK, and the EU. We discuss several key legal considerations, including insider trading and material nonpublic information (MNPI), data provenance, data privacy, cross-border data transfers, the questions of exclusivity and AI regulations.

We underscore the nuances of materiality and the evolving regulatory landscape, especially in response to issues such as data privacy and sensitive data. While the US relies on a more case-law-based approach, the EU and the UK have introduced comprehensive regulations, such as the Market Abuse Regulation (MAR) and the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), to harmonize and strengthen their data compliance frameworks.

Join Eagle Alpha in New York on January 18th, 2024 for their upcoming Alternative Data Conference. Register your interest here.

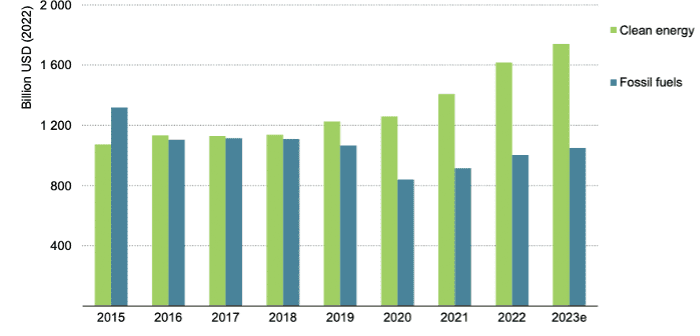

Figure 1: Global Energy Investment in Clean Energy and in Fossil Fuels (Source: IEA)

According to the IEA’s Stated Policies Scenario, the demand for coal peaks in the next several years, the demand for natural gas plateaus by the end of the decade, and the demand for oil peaks in the middle of 2030s before starting to fall: “The result is that total demand for fossil fuels declines steadily from the mid‐2020s by around 2 exajoules (EJ) (equivalent to 1 million barrels of oil equivalent per day [mboe/d]) every year on average to 2050.”

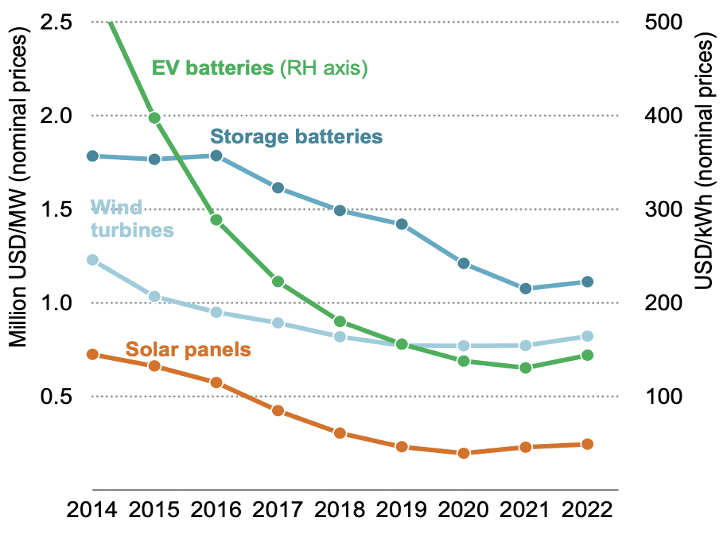

Several factors have contributed to the boost in clean energy investments. The rate at which renewable energy prices have fallen over the last decade has been a game changer, making it comparable in cost to building new coal and nuclear capacity. Improved economics coincided with high and volatile fossil fuel prices and with improved policy support like the US Inflation Reduction Act.

Changing consumer preferences played a role in the shift towards EVs. As more automakers introduce a wider variety of EV models, including SUVs and luxury vehicles, consumer choice has increased, appealing to a broader range of preferences and budgets. The growth of charging infrastructure is also removing one of the primary barriers to EV adoption – range anxiety. Figure 2 below shows that average prices for clean energy technologies have fallen significantly in recent years.

Figure 2: Average Prices for Selected Technologies (Source: IEA)

Climate Policies and Regulations

The Paris Agreement, a legally binding international treaty on climate change, was adopted by 196 parties in 2015 and came into effect in 2016. The primary objective of the Paris Agreement is to limit global warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, with an aspirational goal of limiting it to 1.5 degrees Celsius. This is crucial to avoid the most catastrophic effects of climate change.

It has had a significant impact on national policies and actions related to climate change in countries around the world. However, climate policies and regulations vary significantly across the world due to differences in government priorities, economic conditions, and environmental challenges. For example, republicans in the US passed a sprawling energy bill in March 2023 contesting that President Biden is too reckless in his desire for a quick transition away from fossil fuels.

The US Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 (IRA) is a comprehensive climate law with various energy-related tax incentives designed to combat climate change. According to the Roosevelt Institute, this legislation will shape the US markets and influence future generations. In August 2023, the Department of Energy reported 157 applications for clean energy projects totaling over 140 billion USD in loans.

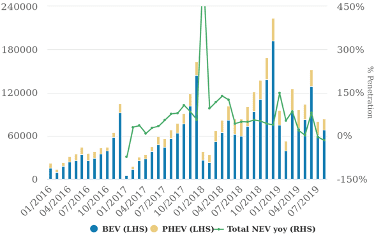

UN Secretary-General António Guterres urged countries, responsible for around 80% of global emissions, to accelerate emission-cutting efforts. However, major G20 nations like China, India, and Indonesia argue that aggressive emissions reductions could harm economic development. Cuts in new energy vehicle (NEV) subsidies in China resulted in a significant drop in sales which shows that it is essential to subsidize new technologies until they become cost competitive (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Cuts in NEV Subsidies Led to Sales Decline in China (Source: Morgan Stanley)

There is a lack of consensus, however, on how quickly the transition to renewable energy should occur. According to the IMF, accelerating carbon emission reduction targets may lead to unforeseen macroeconomic disruptions. The scale and speed of the transition, which aims to transform a $100 trillion global economy within a quarter-century, pose unprecedented challenges. The uncertain pace of technological advancements and the divide between advanced and developing countries on priorities also pose significant challenges.

Alternative Data Availability

Several alternative data categories can be useful when analyzing energy markets.

Satellite data, also referred to as geospatial data, is photographic images collected by satellites orbiting the Earth and can be enhanced with data from drones and radar. Satellite imagery can track the construction and expansion of energy infrastructure such as power plants, wind farms, and solar installations. This helps in estimating the future energy supply. Satellite data is also increasingly used in oil and mineral exploration, land mapping, maritime operations, and in infrastructure management. ESG compliance and anti-greenwashing efforts create further demand for satellite imagery as it can be used to set benchmarks and measure the impacts of companies.

Understanding global commodity flows involves examining economic trade data which involves information on a specific commodity’s size, volume, mode of transportation, and market value. As such it is an important economic indicator of businesses, trade, and economic growth. The data is compiled using a variety of different sources. Some of these sources include online resources, government, public data, shipping firms, logistics companies, and transportation organizations.

Disruptions or bottlenecks within the supply chain can impact a company’s ability to deliver products on time, potentially affecting revenue and customer satisfaction. Energy companies are under increasing pressure to reduce their carbon footprint. Supply chain data and ESG data can be used to assess the environmental impact of various suppliers, transportation methods, and materials, helping companies make more sustainable choices.

Weather and climate data can be utilized to understand the impact of weather on investable assets, manage and mitigate weather & climate risk, generate trading signals, portfolio alignment with climate trajectories, and scenario planning. Weather data is essential for forecasting renewable energy generation, such as solar and wind power. Energy companies use historical weather patterns and real-time meteorological data to predict energy production, helping them balance supply and demand more effectively.

Furthermore, energy companies must adhere to a complex web of federal, state, and local regulations. Legal and regulatory data is used to monitor compliance with environmental, safety, and operational requirements. Non-compliance can result in fines and legal action.

For more information on the data sources mentioned in this article and recommended third-party data providers available to view on our buyer platform, please reach out to dallan.ryan@eaglealpha.com.

Conclusion

Investing in the energy sector is undergoing a profound transformation. While traditional fossil fuels have historically dominated, the rise of renewable energy sources and the urgency to combat climate change are reshaping the landscape. However, this transition is not without challenges. Regulatory uncertainties, geopolitical events, and varying opinions on the pace of change create a complex investment environment. As the world continues to grapple with energy-related issues and strives for a greener future, investors must adapt to these changing dynamics with alternative datasets helping to navigate the evolving landscape.